In October of last year, former fanzine writer and current psychiatrist Michael Tau combined his two disciplines to create his first book, Extreme Music: From Silence to Noise to Everything In Between. “At the core, the book is driven by my curiosity about some of the unusual and extreme music that I had been exploring over many years,” Michael tells us. “I got into experimental music when I was a teenager listening to a radio show called Brave New Waves, which would’ve played from midnight until four A.M. So, I used to tape it with cassettes [Laughs] from the radio.

“And then, throughout my high school years and beyond, I would write about, interview and review music, including a lot of music on the experimental fringe, but I always found myself fascinated by…wondering what the stories are behind some of the more extreme and unusual musical concepts that have been produced, and the stories behind them [and] the motivations of the people behind these things.”

The Extreme Music project began in 2016 and wasn’t completed until 2020, as Michael worked on the book in the background of his day-to-day life of psychiatric care and being a father. With no publisher with set deadlines and expectations, Michael would cold email various producers, artists, labels and fans to gain a greater understanding of the appeal of the music which he was listening to and reading up on in his spare time.

“I think one of the things that’s easy to misunderstand about the book is – and this is my folly in calling it Extreme Music – is that you read it and you would assume that it’s going to be a description of extreme metal genres, or power electronics. Genres that are extreme,” says Michael. “Whereas, really, the book is about conceptual extremes as they manifest in the music world.”

After much study, writing and curation, the finished book explores various genres with their focus on loudness (harsh noise wall, noise music), quietness (lowercase, ambient, drone, Onkyo), vulgarity (pornogrind, grindcore) and quickness (splittercore, speedcore), as well as looking at extreme packaging, production, recordings, technologies and more. It’s a very thorough examination of music and peripherals which could be considered “extreme.”

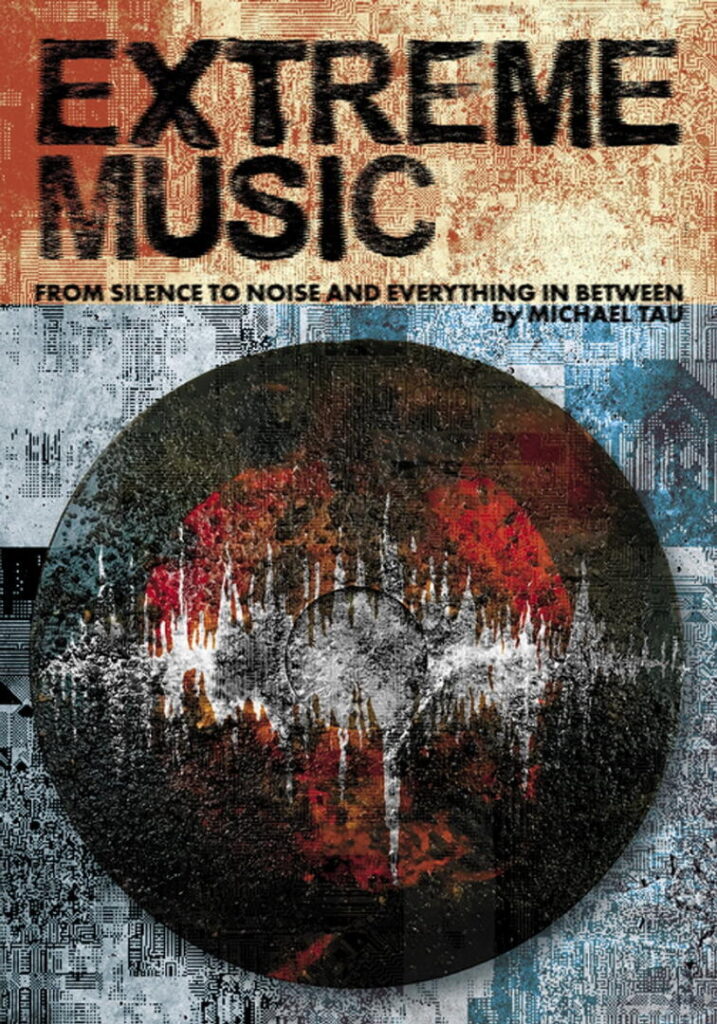

Courtesy of Discipline PR

“The book would evolve as I’d learn more from the people that I was interviewing,” continues Michael. “’Cause before you hear the words of the people behind the music, you often carry all these assumptions about where they’re coming from, and then you might be completely wrong. So, when I would interview people, I would always ask them – whether it was an email interview or Zoom or Skype or whatever – I would ask, ‘Tell me about your life outside of making music. Roughly how old are you? What do you do? Do you have family?’ I would say, like, ‘You can tell as much as you want. Like, [I] respect your privacy, but tell me what you can.’ When we hear about someone making harsh noise wall, and we know nothing about them, our mental image fills out so much when we find out just a little bit about who this person is, right?…And I just find that helps us feel a sense of story, which is ultimately what makes most writing interesting, I think.”

While the book generally takes a neutral perspective of the music covered (save for a few choice adjectives here and there), there were certain areas which Michael didn’t wish to explore: “The one thing I chose to not include in the book was, like, any music that was affiliated with Nazi scenes, white power scenes, these sorts of scenes. Because there are examples of packaging, unusually packaged music, within the genre, but it’s just something that A) I don’t consider integral to the concepts of the book, and B) Not something that I wanted to be in my book, so that was an editorial exclusion…A) I didn’t want to explore it myself, and B) I didn’t want to be disseminating it.”

With the acknowledgement of the importance of recognising editorial influence from the previous paragraph in mind, the themes of ethics and responsibility is something which Michael, given his profession, is very considerate of, and the book touches on this a lot, especially when tackling genres which rely on the distribution of lost tapes – which could be anything from simple grocery lists to full-blown personal diaries – and recordings taken of people without their knowledge, especially of those with mental health issues.

As for his future publishing plans, Michael says, “I have ideas for books which I think would be interesting topics, and I’ve even done some initial interviews and research. My job is very busy and I have a child, so my life is very busy, so I have much less time than I used to, to work on this, and my style was to write the book without necessarily having a publisher and seeing if anyone was interested, so that would probably be the tact I would take the second time around as well, ‘cause I think it would be really hard to manage under a deadline. But, then again, maybe all books will be written by A.I. in a few years!”

Michael Tau’s book Extreme Music: From Silence to Noise to Everything In Between is out now on Feral House and is available to purchase here. For a much more extensive look at this interview where we expand on the topics discussed, in addition to talking about ethics, Michael’s background, A.I. music, more extreme music, among other things, check out our latest edition of POSTBURNOUT.COM Interviews…, which premiers today at 17:00 (IST) on YouTube and available everywhere else afterwards.

Aaron Kavanagh is the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Post-Burnout. His writing can also be found in the Irish Daily Star, Buzz.ie, Totally Dublin, The GOO, Headstuff, New Noise Magazine, XS Noize, DSCVRD and more.

POST-BURNOUT

POST-BURNOUT