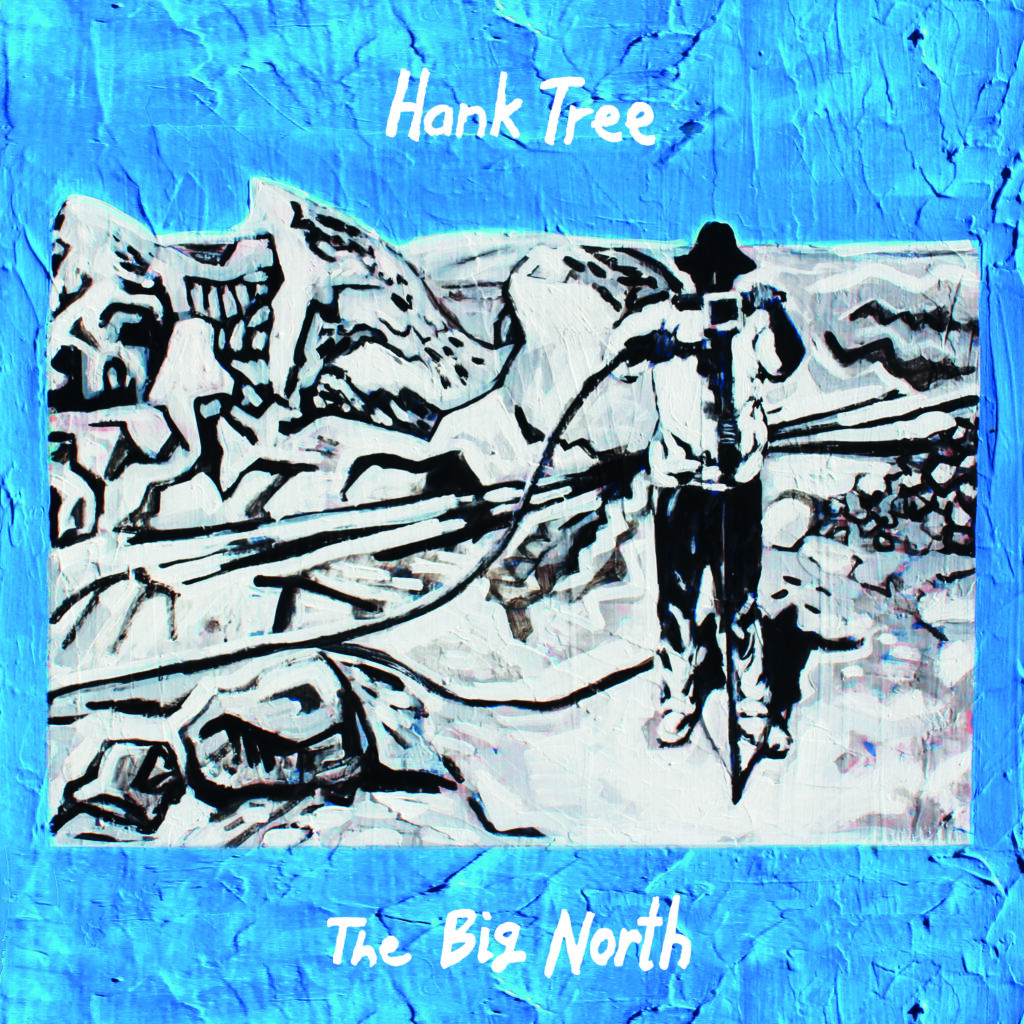

In this interview for Post-Burnout, Scottish indie musician Fergus MacDonald speaks with Aaron Kavanagh about his new band Hank Tree, the release of their debut album The Big North, how the history of abandoned towns in northern Chile inspired the album, working with producer Andy Bush, how Father Ted inspired the band’s namesake and how Lewis Capaldi’s canceled tour dates during the pandemic helped to get the album finished.

—————-

The first thing I wanted to ask was, for you yourself, how exactly did you get into music? How did you become a musician yourself, and how long have you been at it?

Quite a long time. I know quite a lot of people who’ve played in bands through the years and maybe drift away from music a little bit, and I’m probably the opposite in some ways. I did start playing in my first band when I was 18. [Laughs] That’s going back quite a long time, now. But, yeah, I played guitar at that point and, yeah, for years I was mainly just contributing to other people’s music. In the last few years, I kind of decided at some point to have a shot at writing myself; I didn’t really have the confidence to do it before then. So, yeah, the thought of starting something myself from scratch and sharing that with other people, that’s really something that I’ve just done in the past few years. I’m not from a musical background in the sense that I didn’t study music or I can’t read music or anything like that, but it’s mainly been a passion in my life that’s become stronger through the years, to the point where I can’t imagine not wanting to do music. I have to admit, I had a few years where I wasn’t playing in bands and I moved abroad, and I did really miss music and I got a renewed appetite for putting energy into creating things after that break.

So, if I’m to understand correctly, it was self-taught, learning guitar?

Um-hum.

I was wondering, was it through reading tabs on the internet, or how exactly did you begin and what were you listening to that inspired you to take up the guitar in the first place?

I had some lessons when I was growing up, just learning chords and things like that; more basic stuff. I did start playing guitar when I was really young, like six or something like that. I remember seeing people like Elvis and Jimi Hendrix on TV and being kind of fascinated by it – particularly Jimi Hendrix smashing things up; that appealed to me as a six-year-old [Laughs]. And just his very colourful dress and everything about seeing him seemed very exotic. Well, I was brought-up in a small village in the northeast of Scotland. It was a fine place to grow up and everything like that, but maybe not the most exciting? [Laughs] So, seeing something like Jimi Hendrix was very exciting and I wanted to be more like that kind of guy. Not that I’m particularly like Jimi Hendrix now [Laughs], but the desire to play music came from that. I did get in – maybe in my teenage years – when more people were putting tabs and stuff online, that was quite helpful. I listened to a lot of people like Nick Drake and Elliott Smith around that time and, yeah, that was a good way for me to learn their music. When I was a teenager, as well, I had an attempt at studying music at school, which, it didn’t really fit with me, but I did get the chance to, like, borrow a four-track cassette player as part of that and work on some of my own stuff, so that was quite important to me: that I had even just a basic facility and that I could start layering things up and just seeing what was possible on my own. And, yeah, that’s kind of stuck with me; I still like to do that now.

Your new project is called Hank Tree and you’ve come from the State Broadcasters, which is your previous band – and there is a huge pedigree to this band, like all the musicians have been involved with several different projects – but, in your mind, how do you feel that this one differs from those?

Eh, yeah, this one is a lot more personal for me, just because it was something that I’ve started myself. State Broadcasters, I was playing guitar and some other instruments, and that was great, and I still do some other projects with people from State Broadcasters, so the relationships survived, and I really like the songwriter who did the songs for State Broadcasters. But, yeah, I felt like at some point I wanted to do more and kind of push myself a little bit more and see if I could do things myself. So, Hank Tree kind of started more as a solo project and, over time, more people have got involved. The first thing that we put out was an EP, about four years ago I think, and that was basically just me and a couple of producers that worked on it, but, in more recent years, when I’ve been trying to gig,..Roy Shearer got involved, who’s our drummer. I’ve seen him play with various other bands around Glasgow and, now in the last year, Bart Owl who played in eagleowl is involved and, even more recently, Faith Eliott, who’s a singer-songwriter, played [their] first gig with us last week. So, I don’t think we’ll be adding any more people in the near future [Laughs], but it’s been interesting to kind of get used to different responsibilities in the band, where, in the past, you’d take the lead from other people and, in this project, I need to…yeah, I don’t know. Sometimes, I feel like I can be a bit of a fascist, in the way that I feel like I need to be deciding on things [Laughs].

Sure [Laughs].

Which takes a bit of getting used to, where you can feel you’re being a bit of a dick sometimes, if you’re deciding on the set and involved in all aspects of the way something’s presented. But, yeah, I do put a massive amount of energy into this project in a way that I haven’t in the past. Yeah, it’s definitely my main musical focus these days and, if I’m doing other things, I’m always thinking about, “Oh, is that going to distract me from doing Hank Tree stuff?” I wouldn’t want to do too much of other projects now, because, yeah, this is my thing now and I want to build-up a body of work using that name and, you know, gig as much as we can and gather momentum and all these kind of things.

Photo credit: Greg Ryan. Courtesy of Olive Grove Records.

Could you explain the name “Hank Tree”?

The name?

Yeah.

[Laughs] Eh, yeah. It’s a bit of a daft name, to be honest. It’s a Father Ted reference. [Laughs] I’ve been a Father Ted fan for as long as I can remember. Eh, yeah, at some point when I started recorded demos at home and the time came that I should send things out to people, I hadn’t really thought about a name, so I kind of just had to decide on one without giving it that much time, to be honest. I didn’t want to use my own name, partly because it sounds almost like a folk musician’s name, and there is a folk musician with my name! [Laughs] So that could get confusing and I don’t think that my own name…Yeah, I think there may be connotations to my name that wouldn’t really match with what the music’s actually like, so it made sense to have a different name. And also now, I wanted to feel like the project could be a bit more fluid and, while it started as a more of a solo thing, I didn’t want to be like a singer-songwriter person just playing, myself, acoustic guitar kind of things; I wanted it to be a bit more collaborative, even though I would be taking the lead. So, yeah, in the case of Hank Tree, I’m not sure how familiar you are with Father Ted…

I grew up with it [Laughs].

Yeah [Laughs]. Well, I mean, I’d like to think everyone in Ireland did. Maybe not the case. Depends how religious you are; how blasphemous it is. Eh, there’s the episode where Father Ted gets his Golden Cleric Award and…the mysterious visitor comes to the island, trying to steal his award, and Mrs Doyle has to guess what his name is.

Oh, that’s one of the names she picks, yeah? [Laughs]

Yeah, “Hank Tree” is one of the names. [Laughs] It’s one of the slightly-less outlandish names she uses. I went through the other ones, and there are things like “Hiroshima Twinkie;” seemed like that’s a bit too much. But “Hank Tree” sounded like it could be some kind of vaguely country singer-songwriter. But, yeah, it could be the name of a person, or it couldn’t be. I kind of liked that. I’m not like massively attached to that name, but, yeah, I’ve committed to it now and it’s going to stay [Laughs].

Speaking of the music of Hank Tree, I know it’s kind of hackneyed to be like, “Oh, it’s like X-meets-Y,” but in some ways it kind of does feel like – you mentioned Elliott Smith earlier – and it does feel like if Elliott Smith played flamenco. [Fergus laughs] It feels very rooted in…I found the music from your new album to be very beautiful and melancholic, in a sense that Elliott Smith is, and I think – I didn’t have a lyric sheet when I was listening to the album, so I didn’t want to interpret the lyrics, just in case I got them wrong – but even, I think, without knowing what’s being sang, I think the emotion comes across and it has this real bittersweet expression to it. I was wondering if maybe you could talk on that a little bit?

Thanks. Yeah, with Elliott Smith, anyway, like I said before, he was someone that I listened to an awful lot, as a teenager. I don’t listen to him that much anymore, but he’s probably made an inescapable impression on my brain and what, aesthetically, what I like that there will probably always be a bit of Elliott Smith in there and that I learned to play his songs, so it probably affects the way I play guitar, as well. The comparison with him, I didn’t think about it at the time, but maybe in hindsight, musically, I wanted Hank Tree music to be…to have these different elements and the first element being quite clean and delicate – I play a lot of classical guitar and pick classical guitar – but I like to add things that are a bit messier than that, to kind of sometimes pull the songs in a different direction, so there’s a tension to it. And I think that is something that you get in Elliott Smith music, so, yeah, I guess that would be one thing. Lyrically, the focus on this album was a specific history in the north of Chile. I lived in Chile for a few years and got really interested in the history of a particular area there, in the desert, having spent a bit of time there and, yeah, the history of that was: there was a massive discovery of saltpetre in the area, which meant there was a huge boom in the economy and this desert – which was basically the driest place in the world – loads of towns were built in the desert, in a very inhospitable environment and, yeah, thousands of people moved there from all over the world. That would’ve been late 19th Century. The economy didn’t last that long and collapsed sort of post-First World War, so that towns were gradually abandoned and today they’re basically all abandoned and, yeah, I spent a bit of time in some of those towns, you can walk around and it’s quite surreal, but a very, very haunting place. We have all these towns and the factories that were used – public buildings, swimming pools, theatres, shops, pubs – completely empty and rusting away in the desert. I found it very powerful, visiting these places, and the more I learnt about that history, the more fascinated I became with it. And there is this sort of bittersweet quality to it that was very hard for people living there in a lot of ways; the conditions they were working under and just living in that kind of environment was very hard, but a lot of people loved living there and they built communities that were very closeknit and it was very hard for people to leave; there were even cases of people stay[ing] on after all the electricity had been turned off and things like that. One of the songs was about, there was quite a common practice that, once the towns had been abandoned, some of the residents would go back at dark at night to strip buildings of their materials, illegally. They were taking apart their own towns. It had a sort of bittersweet quality to it. So, I guess, yeah, so many aspects of that history had a bittersweet quality for me and it’s one that I tried to put across into the music. Hopefully, I managed that.

I think you did. I was just curious, what brought you to Chile to begin with? Do you, for example, speak Spanish? ¿Hablas español? Like, were you versed there, or were you just kind of going as a trip?

I speak OK Spanish, now; I kind of get by. When moving over there, I didn’t speak [it] at all. My now-wife speaks Spanish and spoke Spanish well then. I partly went just out of a bit of a sense of adventure. At the time, I was working lots of jobs in, like, the hospitality industry and things like that and not finding that very rewarding. I was doing music at that point as well, but, yeah, we both wanted a bit of adventure and something else for a while, so we went out there partly because we heard there was a possibility to make a living from teaching English and that kind of thing; there were enough people wanting to learn. And I was keen to…I’ve always been interested by Latin America, and it seemed like an exotic far-off land that I’ve always wanted to go to. So, we kind of went out there, one-way ticket, and just seeing if we could make a go of it, and, yeah, we stayed for three years in the end. Yeah, I miss it now. We’ve been back in Scotland for a while now, but, yeah, we’d like to go out again at some point.

I don’t know if it’s the same in Scotland, but, in Ireland, we have a very sizable South American population; primarily from Brazil, but we also have people from Chile, Argentina, Venezuela and so on. I don’t know if those cultures are also existent in Scotland?

Eh, I think there’s quite a small Latin American [community]. I know a few people from South America around Glasgow, but not often. The times in the past where, say, we’ve been sitting in a pub and I could hear someone with a Chilean accent or a couple of people speaking to each other, it is a bit of a surprise, ‘cause it isn’t something that you’d hear every day. We get lots of people from Spain – particularly in Edinburgh, there’s loads of Spanish people – but, yeah, it seems a strange move to me. I know my brother’s girlfriend is from Brazil and getting used to the environment in – I mean, it’s the same; Scotland and Ireland are pretty much the same environment, raining all the time! We’re very close neighbours! – I quite respect their [Laughs] willingness to give that a go. We’re the other way around of, “I’d quite like to be somewhere where it’s sunny for a while!” [Laughs] And, yeah, I definitely miss that.

Speaking of, so your new album is called The Big North and I noticed that it was produced by Andy Bush, who is probably best known for his work with We Were Promised Jetpacks. I was just wondering, what do you think adding an external producer versus self-producing added to the project?

Em. Yeah, I do feel sometimes that I’m learning how to produce things a little bit, myself, but with the awareness of the skill of being a producer. I do appreciate the level of skill that a good producer has, and that’s not something that I can replicate easily in my flat with my very basic equipment.

Sure.

So, yeah, it depends on the release, I guess. Quite a lot of the songs on the album are, they’re not, like, huge arrangements of big brash bands or anything, but there is quite a lot going on and having an experienced pair of hands definitely helps with that. Yeah, recording drums and things like that, I would have no idea how to record drums. So, yeah, Andy is somebody that I’ve known for quite a while, from State Broadcasters days, in fact, because he used to play in bands more than produce things and, yeah, he’s just very professional and very encouraging and he’s a nice person to work with, very devoted. I feel very lucky to have worked with him because he’s a very busy man. When we started recording the album, it was early 2019, so ages ago, and he was about to start working on tours with Lewis Capaldi, because Lewis Capaldi was just starting then, and it just became harder and harder to record with Andy as Lewis Capaldi became massively popular and he was just on the road all the time [Laughs]. So, in a way, the pandemic made things harder in some sense, but it meant that Andy wasn’t going out on massive tours all the time, so I was able to corner him and I think he was quite happy to have, since a lot of his work had disappeared, to have a project to work on. So, in a strange way, the pandemic kind of helped the album, even if it was quite hard to work around the different barriers that that put in place at different times.

Yeah, and one thing that I thought the album is very successful in, is in creating a sense of atmosphere and ambience. I’ve just noted some little things here from the album, like, for example, “Arriving in the Big North” has a little soundscape of birds chirping, a very subtle thing; “Back to Work” has the sound of water draining; and “Nothing” has, I think it was a swing, it sounded like a rusted swing. I was wondering, were those things your idea or was that Andy’s?

There were my ideas. In the examples that you mentioned, I was keen to – while recording this album, while writing about somewhere on the other side of the world – I was keen to try and not make it too distant; to try and connect it with the place I’m writing about as much as possible. And, yeah, I’m really interested in field recordings and things like that, and, like, incorporating field recordings into things; normally in a hopefully fairly subtle way. The examples that you mentioned, the swinging sound is like a water pump windmill that I recorded in one of the ghost towns. So, yeah, that’s basically the last thing that you hear on the album; I thought that would be quite a nice way to finish things. That last song is kind of meant to represent the emptiness of the places as it is now and, yeah, if you go to these places, that’s one of the few sounds that you can hear apart from the wind clanking around old factories and things. The field recording on “Back to Work” is actually like an industrial machine, a Pelton wheel it’s called, that I recorded in, there’s a museum in Manchester, an industrial museum, and, yeah, like industry is a pretty big theme in the album in general and, yeah, in a very direct way, I wanted to incorporate some industrial sounds in there. There’s dynamite in – a dynamite explosion – in a song that you might not notice is there. That’s on “Another Accident.” The first song, the field recording is more of a public domain recording of the city where I used to live. There’s some great resources for field recording made by like these databases made by very committed field recording experts; there is just so many stuff up there and I found it a real thrill to find these sites where I could hear sounds from the places that I used to live in that are so far away now that I can’t pop over and visit, so you can kind of get quite a nostalgic feel from listening to these field recordings. Andy was really good at editing the field recordings, like, say that last one with the clanking metallic windmill sound, he was able to take out all the nasty stuff. The recording I had was really rough around the edges, because the wind was blowing around that it really made it hard to find a good thirty seconds of the recording that I had. But he was able to work his magic with all these field recordings and make them fit with the songs in a way that I’m really pleased that he managed to do.

I was just wondering, the idea of doing a concept album in this way; is there anything else that would, potentially down the line, inspire you in such a way to commit to an overall narrative in the way that The Big North does? Because one I felt whilst listening to – and I don’t know if this intentionally or just my interpretation – but I feel that the iconography of the album, including not only the album itself and its art, but also the accompanying music videos that you’ve made for the album, I feel, has this kind of feel of a lone wanderer in a Western film, almost, he comes into town; wandering into town. I was wondering how much of that was intentional and how much of it was just sort of how I read it, I guess?

Hmm. That’s an interesting thought. Yeah, I guess, I do remember reading histories, related to the period that I’m talking of, there being a lot of solitary workers who would go these places on their own, like dayworkers. And, yeah, there’s not any songs specifically about those people, but, maybe, yeah, in my consciousness somewhere. Yeah, the [album] cover is a painting based on an archive photography of one worker out with a drill in the desert, mining. Yeah. Hum. I’ll give that more thought, your interpretation, because I like that [Both laugh]. In terms of overarching themes, in general, I tend to write groups of songs, and tend to have a bit of a preference for – I guess some people are more into writing self-confessional, singer-songwritery type songs, which I like, but it’s not necessarily what I want to do – I prefer writing songs about subjects that I’m very enthusiastic about and, generally when I get interested in a subject, I want to learn more about it and get inspired to write about it. I find it hard to contain enthusiasm about a big subject into, like, a four-minute song or whatever; I feel like it makes sense to push it further. In the case of this history, there’s so many aspects of it that I find interesting that’s almost like every song is about a slightly different aspect of it and, yeah, there is a narrative arc, but I think, in the future, I can see me continuing….yeah. I never really think of it as a concept album, but I guess it is. I’m not quite sure what constitutes…Yeah, I’ll need to look at a definition of what constitutes…I mean it’s a history of a very specific…

Well, I would define a concept album as something with a kind of overarching narrative, which I feel The Big North definitely has.

Yeah. Yeah, I guess. For me, maybe the idea of a concept album can have quite negative connotations for some people, for being quite “prog-rocky” or quite overblown. And yeah, [Laughs] I hope that’s not the case.

I’m definitely not accusing you of being prog [Laughs].

[Laughs] Eh, I think all the songs are kind of more intimate moments, instead of one big thing, but, yeah, they’re very connected episodes. I don’t see any protagonist of the songs; it’s not like the same people going through one arc or anything.

Well, I think the location itself is the character.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Yeah, and I guess the history that I’m focusing on, that kind of determines the arc. I’ve not kind of messed around with times. To me, well, to me it makes sense of the kind of people who are arriving in these communities and, at the beginning of this album. The middle is more about work and the realities of life. And then, the final third, kind of the decline of the industry and people leaving and things like that.

And I feel that’s really captured just in the musicality. Towards the end of the album, it gets quite distorted and quite disquieting, in a lot of ways, whereas the beginning of the album has a very – even though there is an underlying melancholy – it’s very chipper and it’s very bright and there’s a focus on acoustic instrumentation and, where in the end, it tends to get quite a little…the whole album tends to get washed with sort of disquieting distortion throughout.

Yeah. I’d say maybe in the middle, there’s one song that’s probably a little bit of an outlier – “Eighteen Pence,” it’s called – and that’s about a massacre that occurred; a massacre of government forces on striking workers that happened in the city Iquique. Yeah, so that was kind of focusing on one of the realities of these places; the work conditions that people had to survive under and what could happen if you’re a dissenting voice. Yeah, so that’s probably a heavier moment in the middle, but you’re right, towards the end, it is more musically things coming apart, more feedback and yeah.

Wrapping up, is there anything you’d like to add before we go?

Oh! “Anything to add”? Kind of hard. [Laughs] I’m even trying to remember what I even rambled on about [Laughs]. Basically, I suppose I should talk about plans a little bit. We’ve launched the album last week, with a gig in Glasgow, and we’re hoping to play more gigs over the while. It’s very much my thought of, I see with some bands, when they release an album – and in my case as well, I’ve been working towards releasing this album for absolutely ages; I decided that I was going to write about this subject in late 2015 – and I think you sometimes see with other bands that you’ve done all this work into building up to releasing an album, and then you launch it and then go, “Alright, it’s done now. We’re finished.” And I kind of feel like I’ve put so much work into getting to this point of releasing it, it’s the first album of songs that I’ve written myself, so I want to keep sharing it with people and help trying to find an audience with it. We’re on a smaller label here in Scotland, Olive Grove Records, who are great; Lloyd [Meredith] is the guy that runs it They’re very enthusiastic, but I think everyone on the label doesn’t do music as their full-time career, so it can be hard sometimes, finding ways to reach as big of an audience as we can.

Hank Tree’s debut album The Big North is available now on Olive Grove Records. You can stream it or purchase a copy here. You can also follow Hank Tree on Facebook and Instagram.

Aaron Kavanagh is the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Post-Burnout. His writing can also be found in the Irish Daily Star, Buzz.ie, Totally Dublin, The GOO, Headstuff, New Noise Magazine, XS Noize, DSCVRD and more.

POST-BURNOUT

POST-BURNOUT